Writing about his experience studying in France, the symbolist poet Li Jinfa (1900–1976, né Li Shuliang) explained the origins of his peculiar pseudonym, “Jinfa” or “golden-hair”: “How my pen name came about was entirely the result of a dream,” he recalls one day spent with friends in Paris’s Hôtel le Sénat in the summer of 1922 (Yang 1986: 57–58). Suddenly overcome with dizziness while taking a walk, the young man was struck with a fever for days, during which a “golden-haired goddess dressed in white” visited his dreams numerous times and led him on hallucinatory journeys through the heavens. After his miraculous recovery, Li Jinfa attributed his survival to the anonymous female divinity and thought it only fitting to honor her by referring to her golden tresses in his pen name.

Before arriving in France in 1919 at the age of nineteen to study sculpture, Li Jinfa, who was born in Meixian, Guangdong province, had never written poetry and spoke no French. He and his Chinese work-study compatriots were sent to a middle school in Fontainebleau to learn French with one French-Chinese dictionary to share and no actual teacher. His tale of being saved by a golden-haired goddess reveals the loneliness of a penniless young man in a foreign land who spent his days and nights reading novels and wandering around in museums (Yang 1986: 57–58). The narrative also reveals the poet’s discursive authority: Li Jinfa the storyteller appropriates the mysterious healing power of the white female body to perform the momentous act of naming himself.

Li’s account of his hallucination, although uncanny, is by no means exceptional in its representation of the beguiling nature of the white Western female body. This recurring figure is especially prominent in the literary and artistic imaginary of Chinese writers and artists who traveled to Paris during the Republican era (1912–1949). In this essay, I address the question of why these representations of white women were so pervasive from the 1920s to the 1940s, during a period of intense political turmoil and anxiety about national sovereignty. The modern literary and artistic figures discussed in this study were chosen on the basis of how they positioned themselves, to varying degrees, as politically detached from the larger revolutionary project of national salvation. At the same time, they were deeply invested in their respective roles as cultural middlemen between the West and their home country of China, an honorary status bestowed on them because of their overseas experience. The members of this eclectic group—the translator and art critic Fu Lei (1908–1966), the writer Xu Xu (1908–1980), and the painter Chang Yu (1901–1966)—all insisted on the potential compatibility of classical Chinese and Western aesthetics. Traveling to Paris at various moments from the 1920s to 1930s (Chang Yu remained there from 1921 until his death), the figures at the center of this study shared a reluctance to give up their attachment to a wenren (literati) sensibility—in many cases, an imagined or learned attachment that manifested itself in their creative work. For the purposes of this essay, I define wenren sensibility as a fluctuating set of cultural connotations specific to an elite, intellectual social class that extend beyond the conventional designation of politically active scholar-officials trained to pass the imperial examinations through the practice of calligraphy and the study of the Confucian classics. Drawing for cultural capital from recognizable attributes of the intellectual elite or of the traditional wenren, these travelers cultivated a distinctly new wenren sensibility that encompassed a range of malleable identities in the face of encroaching challenges such as Western imperialism.

As the literati’s social status declined and their culture waned in the early twentieth century, wenren affiliates felt threatened by the rise of modernity and consumer culture in China. Here, the term “wenren affiliates” refers to those modern intellectuals who, in most cases, despite not having received formal training in the Confucian classics, calligraphy, and painting, were influenced by classical art and literature and attempted to represent literati culture and its aesthetics in their work. The modern intellectuals addressed in this essay intersect in their use of the ambivalent figure of the western European woman in their literature and art as a bodily site of experimentation, and their reliance on traditional Chinese art theory as the root of a spiritual sense of the self. I begin with a brief discussion of literary representations of white women from the late Qing through the 1920s and 1930s in order to examine the kinds of continuities that persisted and to identify new developments. The way in which male intellectuals during the Republican period viewed their social position in relationship to Western women shifted from the perspectives of late-Qing wenren travelers to France, such as the translator Wang Tao (1828–1897) and the diplomat Chen Jitong (1851–1907). During this time of significant cultural transformations, as the boundaries between the binaries of race and ethnicity (white vs. Asian, Chinese vs. French), gender roles (male vs. female), and temporal modalities (modern vs. traditional) grew increasingly blurred, Chinese male intellectuals located an ideal site for self-definition: by depicting the body of the white woman, the modern wenren could make out his own form by emphasizing what he was dearly not. In the essay, I explore the various cultural connotations of literati culture as a concept in flux during the Republican period and argue that this diverse group of modern wenren affiliates, from Fu Lei to Xu Xu to Chang Yu, used literary and visual representations of the white female body to reinforce their masculinity and to recover their displaced cultural and gender authority.

Shifting Ideals of Wenren Masculinity and the Image of the Exotic Western Woman

The eroticized white Western female body began appearing as a key narrative element in travel accounts written by male intellectuals in the 1860s. Xiaofei Tian (2012: 202) demonstrates how late-Qing Occidentalism manifested itself in “negative eroticization” by way of “emphasizing, exaggerating, and dramatizing the sexual depravity perceived by the Chinese travelers in foreign countries,” a practice conventionally associated with Western colonial discourse. Descriptions emphasizing the bodies of western European women abound in travel literature by Wang Tao, the Shanghai-based translator who worked for the London Missionary Society Press and served as assistant to the missionary, sinologist, and translator James Legge. in his description of a Paris cabaret, for instance, Wang Tao praises the dancers: “The actresses were all beautiful and lovely. When they went onstage, they bared their bosoms and shoulders. Their jade like flesh and the lamplight reflected off one another like arrows.” He likened their colorful costumes and the “beauty of their snowy-flesh, their pretty, flower-like faces” to “fairies descended from heaven” (Teng 2006: 113–114). Western women were also routinely depicted as objects of desire sexually available to Chinese male travelers in the literary accounts and illustrations published in Shanghai’s Dianshizhai Pictorial, and often any moral judgment was expressed only implicitly. One anonymous traveler’s account, which was published in 1888 to accompany an illustration of “Western Women Selling Wine,” described the bar atmosphere in France as “an overseas paradise”:

[T]here were several beautiful girls, about sixteen or seventeen years old, with powdered faces and painted eyebrows, running around serving the customers. If any of the customers looked at them attentively, the girls would sit down and join them. There were many guests there, and the place was permeated with the fragrance of musk and orchid, everyone flirting and bantering, and enjoying the wind and the moon [romance] without inhibitions. (Teng 2006: 114)

During a time when gender segregation by sex was still widely practiced in most of China, at least outside of the brothel setting, these early travelers seem as impressed with the exotic beauties as they are with the overall mood of harmonious sensuality, made possible only by the willingness of western European women to put themselves on display for the voyeuristic pleasure of the Chinese travelers.

The body of the white woman was frequently invoked in juxtaposition with the body of the Chinese woman, the latter whose subordinate role under the Confucian patriarchal hierarchy was called into question first in the Western missionary discourse in the nineteenth century and then in the first two decades of the twentieth century by male reformers and radical intellectuals who believed that Chinese women’s “backwardness” was an impediment to China’s modernization. Chen Jitong, who served as a diplomat in France under the Qing government and who arrived in Europe in 1875 with China’s first official delegation, took a slightly different approach to the white female body. Chen lived in Paris for fifteen years before returning to Shanghai and his first book. Les Chinois peints par eux-mêmes, was published in 1883. Like Lin Yutang, who would follow in his footsteps a half century later with My Country and My People (1935), an instruction manual of Chinese culture for American readers, Chen used his position as an outsider in France to give French readers an insider peek at Chinese culture. In his introduction, he writes,

I propose in this book to represent China as it is—to depict Chinese manners and customs by means of my actual acquaintance with them, but in a European spirit and style. I desire to place my native experience at the service of my acquired experience; in a word, I think as a European would who had learned all that I know concerning China, and who wished to draw those parallels and contrasts between Occidental and extreme Oriental civilizations which his studies might justify. (in Yeh 1997: 438)

His goal of smoothing out the incommensurability between gender roles in Chinese and French cultures required that he fully understand both cultures, yet ironically this position of supreme confidence rendered both Chinese and French women the inaccessible Other.

Chen’s chapter entitled “Women” challenges the pervasive French perception of Chinese women as backward, particularly regarding the practice of foot-binding. He argues that the inherent unknowability of Woman is a shared connection between the two cultures, “Without a doubt our [Chinese] woman does not resemble the western woman, yet she is still a woman with all that she cannot be defined by. . . they are all daughters of Eve” (Tcheng 1884: 57–58). Chen also emphasizes the distinct roles played by Chinese men and women in the public and private spheres, declaring confidently: “That the [Chinese] woman frequents neither ministers’ anterooms nor the international receptions where her European counterpart adorns herself with all of the seductions of her sex to charm the society of men, she does not regret. Her life does not have any significance from a political standpoint, and the men can conduct their business” (60). However, he warns ominously, “Cross the home’s threshold, you enter her domain and she rules with an authority that certainly is not given to European women!” (60–61) and, as the reader infers, not given to Chinese men either. To highlight the agency of Chinese women in the domestic sphere, Chen must depict French women, specifically French wives, as essentially powerless beyond their flirting skills: “In France, the wife follows her husband’s position in the social sphere; there is no place in the world where she is more subject to her husband. I naively believed that this social sphere had a wide range until I finally realized that one had to study the law to know that it gives no power to the wife” (61). Chen Jitong’s explanation of French women’s subjugation implies that a Western woman’s sexuality is wasted, because ultimately she is granted no power in the public or private sphere. Furthermore, in being confined to the private sphere, Chinese women actually retain an authoritative energy for the more meaningful task of household management.

In these late-Qing male wenren representations of the white female body, reactions range from aesthetic appreciation to sexual desire to moral indignation and disdain. These examples also reveal the crucial hold the exotic female Other occupied in the traveler’s imaginary and foreshadow how the wenren’s role would become increasingly tenuous in the decades to come, especially for those operating as cultural middlemen. Catherine Vance Yeh (1997: 429) has pointed out Wang Tao’s morally compromised social status as an employee of the Missionary Press in the Shanghai concessions: “Wang Tao was regarded by the wenren community residing in the walled city of Shanghai as a man who had forfeited the self-respect of a scholar for the sake of regular wages; they shunned his company.” Likening the Shanghai wenren to the courtesan, Yeh points out that the wenren’s independence was a product of Shanghai’s semicolonial legal and economic system, a system that permitted Wang Tao to participate in the dissemination of Western thought and commercial culture, but at the cost of his self-confidence getting “shaken by being a salaried employee in the service of foreigners” (433). Similarly, upon returning to Shanghai from Paris, Chen Jitong became a liminal figure, one whose peculiarly French interpretation of Chinese culture was a way of assuaging his fear of betraying China: “Although he was probably the most Westernized Chinese of his time he soothed his conscience by taking a patriot’s stance and writing Western works with a Chinese purpose,” writes Yeh (443). Chen Jitong’s promotion of the woman’s role at home is aligned with this deeper “Chinese purpose,” a rhetorical strategy that rescues China’s public image, at the cost of the French woman’s body.

The young male travelers treated in this essay belong to the generation after Wang Tao and Chen Jitong and were members of an intellectual class whose relevance to modern Chinese society was being questioned in the 1920s. In the aftermath of the abolition of the civil service examination system in 1905, some intellectuals responded to the rapidly changing social and political environment by reinventing themselves with new wenren sensibility that involved a “mastery of foreign languages and knowledges” (Louie 2009: 123). Leo Ou-fan Lee (1973: 38) lists nine qualifications for how to succeed on the literary scene of the 1920s, including, most notably, temperament (“A modern wen-jen should be bohemian, amorous, boastful, lazy but tricky, complaining all the time, and emotional rather than rational”); lifestyle (“He should like modem, fashionable clothes, have gourmet tastes, indispensable habits of drinking and smoking, peripatetic residences, gamble and patronize brothels, have debts, an illness [especially tuberculosis and syphilis], and the ability to chat and meditate”); and social intercourse (“He should have up-to-date knowledge of major trends and configurations on the literary scene, visit literary celebrities, form societies, engage in factional fighting, be able to retain friendly links and make new friends—both national and international”). Although the tone of Lee’s checklist here is decidedly facetious, it insists on the modem and cosmopolitan citizen being at the core of the ideal scholarly persona.

While the traditional-style literati scholar was held up by social reformers and writers as the scapegoat for a feudal society in crisis, his female foil represented the dynamic promise and potential dangers of a progressive and cosmopolitan China. In 1918, May Fourth intellectual reformer Hu Shi described the New Woman in a speech at Beijing Women’s School: “‘New woman’ is a new word, and it designates a new kind of woman who is extremely intense in her speech, who tends towards the extreme in her actions, who does not believe in religion or adhere to the rules of conduct, yet who is an extremely good thinker and has extremely high morals” (Bailey 2012: 62). The New Woman was held up as a positive, hopeful figure that represented a stronger China, and the debate over women’s roles occupied a significant place in the discourse on politics, domestic relationships, education, and biology. Predictably there was no consensus on what constituted the ideal New Woman, and Lu Xun in his famous essay “What Happens When Nora Leaves Home?” (Nuola zou hou zenyang, 1923) proposed that economic independence for women trumped educational level.

Representations of Chinese women in Republican China have been widely discussed in studies on modernist literature and urban culture, especially in the context of literature emerging from semicolonial Shanghai. Nicole Huang (2005: 84) in her book on 1940s wartime Shanghai describes the static image of the Chinese modern girl in relation to the perceived dangers of urban culture: “Often devoid of flesh and blood, these female images were constructed with physical objects or places. In such stories, male travelers to the city visited hotels, coffee houses, dance halls, neon lit streets, brilliant shop windows, and, of course, enigmatic women.” The modern Chinese woman was the source of anxiety for fictional male protagonists, who, Huang asserts, are confronted by feelings of “wonder, fascination, anguish, frustration, confusion, and distress” (84). Most literary studies have focused on the Neo-Perceptionist writers affiliated with Shi Zhecun’s journal Les Contemporains (Xiandai, 1932–1934). In his discussion of the Neo-Perceptionist writers Liu Na’ou and Mu Shiying, Leo Ou-fan Lee (1999: 213) points out the composite quality of their female characters, who are at once Chinese and have Western qualities, such as white bodies, inspired by Hollywood movie stars such as Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford—for example, the hybrid femme fatale in Mu Shiying’s “Statue of a Female Body in Platinum” (Baijin de nüti suxiang). Shu-mei Shih (2001: 298) views Liu Na’ou’s modern-girl archetype as intimately linked to the cosmopolitan urban space of Shanghai: “Both a discursively constructed (borrowed, dissimulated from metropolitan Western/Japanese culture) and a materially contextualized figure (who roams the urban spaces of the semicolonial city), she unsettles the bifurcation of the metropolitan and the colonial.” According to Shih, in Liu Na’ou’s fiction the westernized modern girl, in her ability to subvert tradition, becomes a model for the male intellectual, and acts as a mediator between the male intellectual and Western material culture (299). In these fictional representations, the westernized female body provides a safe space for male fantasy in which the male narrator is allowed to capitulate to the modern girl’s sexual allure, but commits no act of racial betrayal because the racially pure female body is westernized in appearance only.

In the modern Japanese context, a parallel female character archetype has been coined the “Westernesque femme fatale” by Indra A. Levy (2006: 2), who persuasively argues that the cultural hybridity of this character type and “the siren like call of modern Western vernacular writing” are both “privileged objects of an exoticism that underwrote the creation of Japanese literary modernity itself.” Her emphasis on translational processes situates the Westernesque femme fatale in “the interlingual gap between reading Western literatures and writing in Japanese” (2). As much an embodiment of translation as “a form of exoticism that appears to stay at home,” the femme fatale “in fact traverses one of the most confounding of all foreign spaces: the uncharted and unruly expanse that stretched between languages” (2).

Yet existing scholarship leaves one crucial question unanswered: the modern girl as femme fatale is depicted as “Westernesque” in Chinese literature and art, but how is the non-Chinese modern girl depicted in that same context? The few references in scholarship to white Western women occur primarily in studies on the transnational figure of the modern girl, primarily because Hollywood actresses served as models for young Chinese women striving to be modern. Madeleine Y. Dong (2009: 203), for example, writes: “The colonial worship of things foreign (including foreign women) had a strong impact on the modernity of the Chinese Modern Girl.” Publications such as Guo Jianying’s Women’s Pictorial (Furen huabao, 1933–1935) “clearly defined the ideal modern Chinese woman as authentically or properly Westernized in her appearance, behavior, education, and mentality. Using her Western counterparts as role models, the Chinese Modern Girl was expected to be beautiful, healthy, energetic, cheerful, and lively” (Dong 2009: 203–204). Jun Lei (2015: 193) in her article on breast-binding and natural curves has further demonstrated how in the early 1920s, naked bodies of white women were used to “show the natural curves of physically unrestrained feminine beauty in contrast to the unnatural bodies of Chinese women.” All of these scholars interpret the image of the Western female body as having no purpose other than as a modern model for the Chinese female body.

By contrast, in this essay I show that for some Chinese male intellectuals from the 1920s to 1940s, the white Western female also embodied a new kind of possibility, distinct from the ethnographic study and voyeuristic pleasure commonly found in Occidentalist late-Qing travel narratives. Xiaofei Tian (2012: 202) has shown that in late-Qing accounts, “the outcries about moral decrepitude in foreign countries are almost exclusively focused on the female body—from improper attire to its public presence—and on the danger of unchecked female sexuality.” This concern with morality certainly persists in the Republican period, but whereas late-Qing intellectuals were describing women few people knew anything about or had actually seen, by the 1920s, descriptions of the white female body by modern wenren travelers had to compete with the newly circulating descriptions in translated literature, yuefenpai calendars, and women’s journals such as Liangyou.[1] Although the white female body retained its sexual allure, the modern wenren discovered creative ways to take liberties with depicting it and adapting it to suit their individual needs. Instead of merely serving as a point of contrast to its modern Chinese female counterpart, the white female body became a point of focus on which writers and artists could test out and experiment with theories of race and gender, wenren masculinity was called into question in the face of Western masculinity, symbolized by Western imperialism and industrial might. The white female body became one mode for defining Chineseness and wenren-ness, enabling a definition of wenren masculinity (which appeared most frequently in the form of sexual anxiety) by comparing it to what it was not. In other words, during a time when time-established gender and social class boundaries were being challenged by depictions of westernized Chinese modern women, wenren affiliates tried to gain their foothold and redemarcate boundaries by using the doubly Other figure of the white female.

These divergent representations of Western femininity can be read alongside Republican-era discourse about the changing role of modern women, but they also reveal a deeper frustration with the quickly shifting ideals of modern Chinese masculinity. In what follows, I first discuss how Fu Lei used the white female body to accentuate difference and to affirm wenren masculinity as the norm. He comes to define wenren masculinity as everything the white female is not. Xu Xu, on the other hand, created a white female archetype simultaneously disillusioned with medieval European notions of romance and chivalry and attracted to traditional Chinese wenren aesthetics. Finally, Chang Yu used exaggeration and distortion of difference to advocate for a new standard of aesthetic beauty. In all these cases, white woman’s otherness enabled a process of self-definition for Chinese wenren affiliates. Through the new perspective gained by the physical act of travel to Paris, the city believed to represent ultimate creative freedom, Chinese male travelers could imagine the possibility and potential of a renewed appreciation for wenren masculinity in the face of its declining popularity.

Fu Lei: Accentuating Difference, Affirming Wenren Masculinity

In “An Old Dream in June of My Hometown” (Guxiang de liuyue jiumeng, 1928), Fu Lei recounts an experience in Saigon while he was en route to France. Encountering a table of several Asian women chatting in what appears initially to be a simple shop selling Japanese art works but what is actually a multipurpose store, he is drawn to one young woman in particular who is wearing a sheer Western-style dress and studying. He praises her: “With her short hair, pitch-black pupils, her brilliant radiance, she was truly the epitome of the Oriental Girl type” (dongfang de shaonü xing) (Fu 2000: 12–13). Watching the young Japanese woman as she gets up and takes out a Petit Larousse dictionary from the cabinet, Fu Lei excitedly constructs a narrative about her identity: “However, unexpectedly, this virtuous person was made to think of his native home, to daydream of the oriental spirit of this young woman.” More of a nostalgic reflection of himself as a morally upstanding wenren than an imagination about the girl, his fantasy is quickly shattered when two sailors enter and promptly sit down at a table. “That young woman immediately threw down her pen, grabbed a bottle of beer, stood in front of them with a ‘tut-tut’ and popped open the cap. Oh, my dream was shattered to pieces!” His sense of morality is further offended when he discovers another pair of sailors playing billiards in the back of the store, causing him to exclaim: “Oh, to be stranded at the ends of the earth, I fear that I will be planted here at this moment! Woman! Woman! I couldn’t help but draw in a breath of cold air” (13).

This Japanese female in-between figure, neither a white Western European woman nor a modern Chinese woman, initially embodies Fu Lei’s ideal of Chinese femininity as an educated citizen of the world, cosmopolitan in her knowledge of the West and physically appealing in her orientalness. In this foreign country, she transports him psychically to his hometown with her physical beauty, but their sexual attraction is one sided; the reader is given no indication of the young woman’s impression of Fu Lei, if she has any at all. Fu Lei’s description of her opening the bottle and offering it to the sailors reveals his obsession with social status and propriety. He interprets the beer incident as a shocking act of personal betrayal by what seems to be a member of his intellectual class for members of a lower social class. Reminiscent of the Japanese women in narratives such as Yu Dafu’s 1921 short story “Sinking” (the schoolgirls in the street, the innkeeper’s daughter, the waitress at the brothel) who provoke the protagonist’s feelings of inferiority, in this account the Japanese woman reveals Fu Lei’s anxiety about the opposite sex and about his own sexual desirability; although the young woman may appear enlightened and modern, she cannot transcend her deceitful feminine nature simply through education. Her Japanese ethnicity further complicates his horror: he seems at first to consider her a familiar, recognizable type under the category of oriental, but once the young woman reveals her true nature as sexually open to the sailors, she comes to represent the duplicity of all women. In effect, the narrative transforms from an idealized scene of wenren civility (the essay’s title evokes the nostalgic, dreamy mood of a scholar thinking of his hometown) to a nightmare in which the embodiment of feminine beauty chooses a group of boorish sailors over the genteel modern intellectual that Fu Lei believes himself to be.

Born in Jiangsu on April 7,1908, Fu Lei was raised by his mother and his aunt after his father’s early death. His father had been a prosperous landlord, and Fu Lei was tutored at home in Chinese, English, and math before attending elementary school. In the literary canon, Fu Lei is best remembered for his two roles as ideal father figure and translator, although his expertise and interests also included classical music and art. His Family Letters (Fu Lei jia shu) (Fu Lei 2015), a best-selling compilation consisting of more than 200 letters he wrote to his son Fu Cong between 1954 and 1966, shares advice and imparts knowledge on topics such as music, literature, and romantic and familial relationships. In his prolific work as a translator, especially his translation of Romain Rolland’s revolutionary novel, Jean-Christophe, he broke from his predecessor Yan Fu’s (1854–1921) “three principles” (xin, da, ya, or “fidelity, clarity, and elegance”), insisting in his 1951 preface to the second edition of his translation of Balzac’s Le Père Goriot on the importance of shensi, a likeness to the spirit of the original, an aesthetic philosophy rooted in traditional painting: “As far as its effects are concerned, translation should be like copying a painting. What is aimed for is not affinity in shape but likeness in spirit.”[2] Although this section of the essay focuses on Fu Lei’s lesser known travel writings and art criticism, tracing the aesthetic origins of his translation philosophy helps reveal how his depictions of the white female body define him as a modern wenren. By emphasizing the non-Chinese woman’s otherness, accentuating her difference, especially in spirit, Fu Lei is able to uncover the remnants of his own spiritual identity.

As a youth, Fu Lei was very much engaged in the political discussion of China’s uncertain future, and he participated in the labor and anti imperialist demonstrations of the May Thirtieth movement in 1925 while he was a student at Datong University in Shanghai. From 1928 to 1932, he studied art theory and art criticism in France. During this time, he also began translating French short stories. Attending lectures on art and literature at the Louvre and the Sorbonne, he served as Liu Haisu’s (1896–1994) personal translator and lived in the suburbs with another young Chinese artist, the painter Liu Kang (1911–2004). The time he spent abroad introduced him to the latest artistic and literary movements in the West; moreover, his study of Western art at the Louvre, Fu Lei tells us, inspired his love for Chinese painting. In the summer of 1931, Fu Lei’s article “La Crise de l’art chinois moderne” was published in the Paris magazine L’Art Vivant (Roberts 2010: 40–44). Asked by the magazine’s editor, Florent Fels, to write about the state of Chinese modern art, Fu Lei explained to French readers the challenges facing his country: “In today’s China, where people have lived for many thousands of years following wisdom, harmony and the Golden Mean, in the face of Western mechanisation, industrialisation, science and the temptations of material society, it is increasingly difficult, to hold onto a dream-like world of knowing quietude” (in Roberts 2010: 44). The modern material world is presented in Fu Lei’s essay as alluring but ultimately inadequate, ineffectual, and shallow: “To appreciate the causes of the present crisis, be it in the realm of politics or art, it is necessary to look beyond the surface” (40). Fu Lei contrasts the work of late-Qing literati painter Wu Changshuo (1844–1927), which “allows the viewer to apprehend a realm well beyond the material and imbues the paintings with a quality that has the appearance of being simple and unsophisticated (gupu)” (40) with blind imitators and the latest newcomers: “Many young people, however, crave all that is ‘new’ and ‘Western,’ moving too far from their own time and place” (42). Throughout his life, Fu Lei repeatedly sought refuge in the literati tradition from what he perceived as encroaching materialism. In particular, he cultivated a very close epistolary relationship with the literati painter Huang Binhong (1865–1955), whom he met through Liu Haisu, Fu Lei’s colleague at the Shanghai Art School. Claire Roberts’s Friendship in Art traces their exchange of letters, which recount, among other things, Fu Lei’s admiration for and purchases of Huang Binhong’s paintings and Huang’s possible gift to him of additional works.

Fu Lei’s life as an overseas student in Paris was far from one of “knowing quietude,” for he certainly experienced firsthand the exuberance of city life so poignantly described in “Xunqin’s Dream” (Xunqin de meng), an essay published in the avant-garde journal L’Art (Yishu xunkan, 1931–1932). The modern painter Pang Xunqin (1906–1985) traveled to Paris to study art at the young age of nineteen, but he soon returned to Shanghai in 1929 with the hope of creating a modernist art salon in the Parisian style. In 1931, Pang cofounded the Storm Society (Juelan she) with the help of the writer Ni Yide (1901–1970), who had just returned from Tokyo. A year later, in 1932, Fu Lei curated Pang Xunqin’s solo exhibit in Shanghai. The narrator of “Xunqin’s Dream” begins by describing the simultaneous nature of the fragments of urban life: “In Paris, crumbling structures stand alongside brand-new buildings. . . the new, the old, the ugly, the beautiful, things to see and things to hear” (Fu 2000: 95). Enumerating the gritty and glittery attractions of Paris, Fu Lei’s stream-of-consciousness narration ranges from mentions of the city’s diverse and seductive inhabitants to iconic sights such as Montparnasse, the Eiffel Tower, and the secondhand bookstalls along the Seine. Meanwhile, in the middle of this chaos—“all of this spinning and spinning around in the whirlwind in his [Pang Xunqin’s] mind”—the lone figure of the artist emerges: “He, in his black velvet jacket, hat at a half slant, both hands hidden inside his pants pockets, from morning to night, in a half-conscious daze, subsumed by this huge vortex of a world” (95–96).

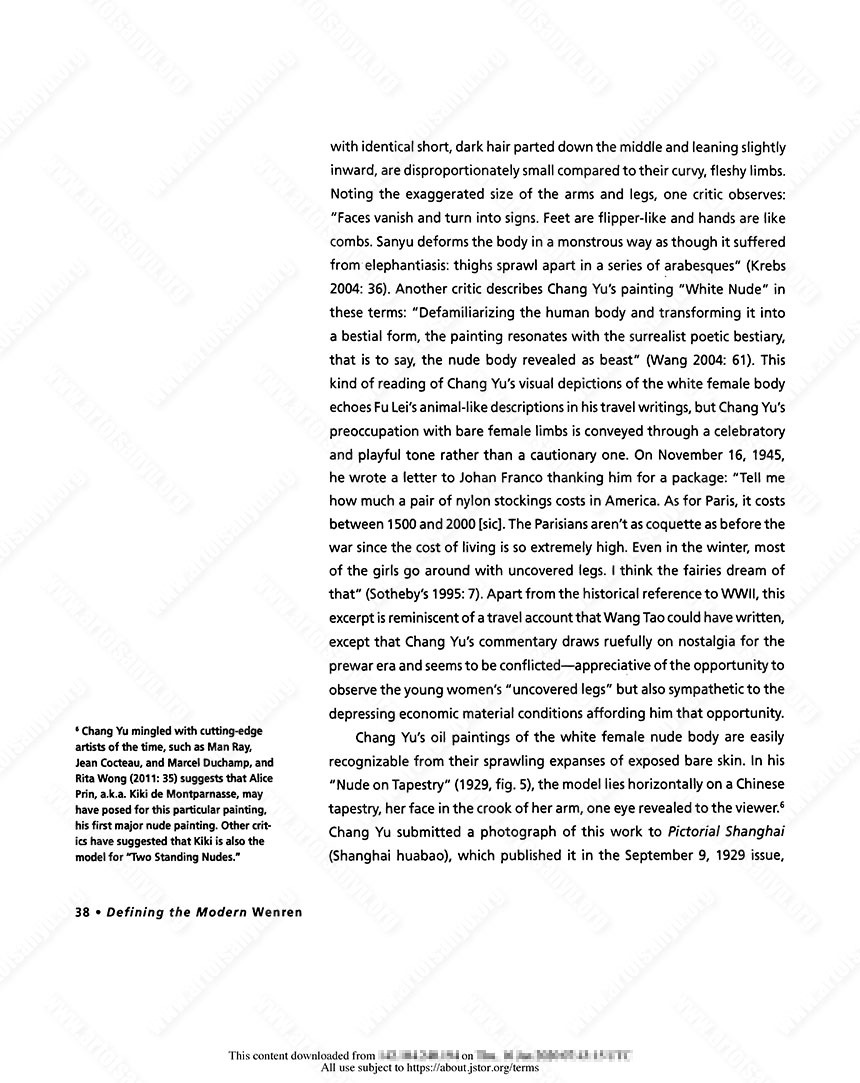

For these Chinese travelers, Paris was a composite of many diverse elements: its eclectic population, landmarks, extraordinary sights, nightlife, all of which envelop its inhabitants in a whirlwind of sensation. Fu Lei lists alongside other attractions the “pretty and seductive demon women,” “dancing girls,” “poules (floozies),” and “charming and elegant maidservants, disgusting landladies,” all circulating in an urban space that is half modern and half ancient, surrounded by “the historical remains of an ancient culture, the passion of a new culture.” The dreamlike images evoked in Fu Lei’s montage about city life, visually depicted in Pang Xunqin’s collage painting “Such Is Paris” (Ruci Bali, 1931) (fig.1), always exist in a feminized space, but this is merely the backdrop against which the detached artist Pang Xunqin finds himself. He is a social outsider, a solitary Chinese male against a dizzying city scape of Western female sexuality. As much as “Xunqin’s Dream” can be read as a celebration of the “exuberance of Paris,” and the default position a traveler occupies in a foreign city, it is at the same time about the detachment required of an artist, or the ideal position of an artist in modern society. Fu Lei introduces the painter by claiming, “From childhood to adulthood, he is the same as all young people; he has dreamed many innocent, magical dreams. His silent disposition, his fanciful sense of humor, cause him to drift further away from reality each day.” Fu Lei concludes with the Chinese saying “One cannot see Lushan [mountain]’s true face by standing in the middle of the mountain” (bu shi Lushan zhen mianmu, zhiyuan shen zai cishan zhong) and applauds Pang Xunqin for his dream: “‘Xunqin’s Dream’ is perfectly situated outside the mountain. This is like Rodin’s so-called ‘human paradise.’ Xunqin, you are so blessed!” (Fu 2000: 97). Being situated outside the mountain or detached from social reality allows Pang Xunqin to view that reality more clearly; detachment leads to a more accurate and perceptive vision of reality. Like the modern scholar, the modern artist must remain objectively detached from his immediate environment. The exotic location of Paris is the ideal space for such detachment: as a Chinese sojourner there, Pang Xunqin will always be an exceptional outsider.

In his own travel essays, however, Fu Lei found it impossible to maintain his neutral and detached tone, even as he viewed himself as an unbiased observer. Fu Lei wrote the letters in Letters on the Way to France (Faxing tongxin) traveling from Shanghai to Marseilles and Paris in 1928; they first appeared serially from January 2 to February 9 in Contribution Daily (Gongxian xunkan), a journal edited by the brothers Sun Fuxi and Sun Fuyuan. Unlike the travel accounts of similar voyages made by Fu Lei’s literary contemporaries Xu Zhimo and Ba Jin, in which the writers focus more on imparting the details of their trip and their new surroundings than on personal reflections, Fu Lei’s letters to curious readers in China relay the experience of overseas travel and include his pointed opinions and observations about food and meals aboard the ship, ship passengers, seabirds, and his lamentations about missing his beloved mother and friends. For instance, in Random Notes Traveling by Sea (Haixing zaji), about his trip to France in 1927, Ba Jin describes coming to shore in Marseilles and provides a transcript-like account of going through customs (Ba Jin 1948: 11: 67–69). And in his unabashed celebration of Paris published as part of his collection of essays of the same year entitled Fragments from Paris (Bali de linzhao), Xu Zhimo begins, “Oh those who have been to Paris could never have a care for heaven, and those who have tasted Paris, to be honest, don’t even want to go to hell anymore” (Xu Zhimo 1927: 1–2).

The details that Fu Lei shares with his readers serve a more practical purpose, because he was motivated by a civic duty to educate readers. His attention to the social reality of his surroundings, particularly class and female sexuality, is most obvious in his discussion of white women. In the second installment of a lengthy piece entitled “Traveling Companions” (Lü ban), Fu Lei focuses his derisory attention on two French women who board the ship in Shanghai on their way to Marseilles. First he tells readers that before leaving China he was warned that “female passengers generally travel in the first two classes because third class is not convenient: only military wives or improper women travel in third class” (Fu 2000: 36). He presents this secondhand information as factual, passing it on to his readers like a piece of insider’s precautionary advice. Instead of steering clear of third-class passengers and following his own moralistic advice, however, Fu Lei spends a substantial amount of time observing the two “improper” French women. Angrily ridiculing the physical appearance and uncouth manners of the two unnamed women to confirm the veracity of the warning, he simply refers to one as “the skinny one” and the other as “the fat one” (36). He likens the first woman to her pug dog, only “not as good looking.” The second woman he calls “ridiculous” and “exceedingly stupid,” calling her a “fat pig.” Unable to insult her sexuality, he resorts to attacking her intellect: “This fat one was extremely stupid; she was not lascivious nor did she seem decent.” But he reserves his most derogatory remarks for her companion: “From morning to night she would just cackle boisterously, and the sound of this wild laughter revealed her crazy wantonness, her indulgent and flirtatious nature. Furthermore, during mealtimes, she would be fluttering her eyes this way and that way at the Spaniard, sometimes even eating fruit, other times pretending to grumble coyly or feign laughter” (36). Here, the French woman is defined in terms of her unnatural sexuality. However, unlike the Japanese woman in “An Old Dream in June of My Hometown,” who is initially described as attractive and only later rendered duplicitous, the representations of the two French women are consistently misogynist and repulsive from the beginning.

Far from tantalizing the narrator with any form of occidental exoticism, the image of the white female body operates here as a visceral confirmation of Fu Lei’s worst fears about class, gender, and race. Depicted alternately as ignorant, hypersexual, animalistic, and immoral, the two French women even have the power to deplete him of his intellectual ambition, as he sputters, “Aiya, I cannot continue writing nor do I wish to! In short, that saying about making someone vomit for three days, nothing fits her as perfectly as that!” (36). This passage, echoing Fu Lei’s earlier refrain of exasperation and defeat—“Woman! Woman!”—at the modern Japanese girl, reveals the perceived damage the women inflict on the wenren’s creative process. All of Fu Lei’s descriptions of the provocative figure of the white woman accentuate her aberrant sexuality as a way to voice his anxiety concerning his own identity as a modern intellectual. Her uncouth behavior interrupts and disrupts his pursuit of writing and reflection, leading him to commit the worst sin of all: losing his ability as an outsider to reflect objectively on reality. At the same time, though, her unnaturalness provides the perfect point of contrast to demonstrate the civility of the ideal modern male intellectual.

Reimagining Wenren Masculinity and Self-Exoticism in Xu Xu’s Xiaopin wen

Like the white women depicted in Fu Lei’s travel writings, the female love interests in Xu Xu’s short stories based on his experiences as a young student traveler in France in the mid-1930s also defy the reader’s expectations of an exotic and alluring femme fatale. The western European women in Xu Xu’s stories are the objects of fascination and sexual desire, but their exoticism, or what makes them distinct from their Chinese counterparts, is that they are drawn to the wenren masculinity of the Chinese narrators in a way that their Chinese female counterparts are not. Instead, it is wenren masculinity that is depicted as exotic, and Xu Xu’s male protagonists, who possess a cultural superiority that the French women simply cannot find in their white European male partners, end up exoticizing themselves to emphasize their own foreignness. These semifictional depictions are much more fleshed out than Fu Lei’s nonfiction observations, extending beyond the surface level into the realm of the fantastic and imaginary.

Xu Xu moved to Shanghai in 1933, after graduating from Beijing University. In the early 1930s he was known mainly for his association with Lin Yutang, the cultural critic for whom he worked as an editor at the Analects school publications. Analects Fortnightly (Lunyu banyuekan) and The Human World (Renjian shi). In the fall of 1936 Xu decided to travel to Paris, where he studied philosophy and became interested in the work of French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941). After the outbreak of the war, he returned to Shanghai in 1938. Although he is better known for his fiction, such as his Ghost Love (Gui lian, 1937) and the novel The Rustling Wind (Feng xiaoxiao, 1944), here I address Xu Xu’s early xiaopin wen, or familiar essays, which were written in the 1930s and subsequently compiled in Fragments from Abroad (Haiwai de linzhao, 1940a) and Sentiments from Abroad (Haiwai de qingdiao, 1940b).

Xu Xu lacked a literati upbringing and formal classical education, yet his adoption of the xiaopin wen as his primary genre plants his work squarely in the tradition of wenren aesthetics, which contrasted starkly with the more mainstream literature in service of mobilizing the masses. Charles Laughlin has aptly described the Analects’ youmo, or humorous, style as an “important premodern counterdiscourse” that “eschewed direct confrontation and instead deliberately turned its attention away from the subjects of writing upon which everyone seemed to be insisting.” [3] Laughlin views xiaopin wen as a genre of writing and a lifestyle, both of which stem from the “literature of leisure” (xianqing wenxue) that emerged in the 1920s, although he locates the belief that literature could serve more than a political aim to as early as the beginning of the seventeenth century.[4] Wu Yiqin (2008: 127) has read Xu Xu’s travel essays as examples of mysterious and romantic entertainment literature praising “the strange” and “western flavor,” yet these xiaopin wen are replete with allusions to classical poetry. For example, in “Autumn in Louvain” (Luwen zhi qiu), the narrator makes frequent references to the autumn poems (shi ci) of Song official/poet Ouyang Xiu and blames his malaise on his desolate surroundings: “In the midst of this kind of fall setting, for someone like me who has just gone abroad, naturally it is easy for me to feel homesick, especially for someone who has this sensitivity toward neurosis?” (Xu 1940a: 14–15). Just as the narrator refers to classical Chinese poetry, so does the travel account recall the genre of traditional travel literature, in which the natural environment—in this case a fall season spent in the dreary university city of Louvain in Belgium—acts as a reflection of the traveler’s inner spirit. Xu Xu’s identity as a wenren affiliate is defined by his choice of genre and the literati sensibility espoused by the semifictional male characters in his stories, in particular “Montparnasse Studio” (Mengbainasi de huashi) and “The Duel” (Juedou) from Sentiments from Abroad, which both address interracial and intercultural desire and challenge the familiar trope of the Chinese male intellectual as sexually inferior.

In “Montparnasse Studio,” the narrator-protagonist, referred to as Z, meets an unnamed French woman at a café after attending a music concert with his Chinese female classmate K. At first Z and K assume that the young French woman is the wife of the Dutch painter accompanying her. Z is impressed that the artist has been in France for only eight months and has already managed to snag a French wife. Perhaps for this reason Z is quite taken by the artist, who presents Z and K with a sketch of them that captures their mood in a startlingly accurate manner. Z initially observes of the woman: “It seemed like she did not have any of the cleverness that most French women have, nor did she have any of the vulgarity found in common French women” (Xu 1940b: 117). The narrator takes for granted the stereotype of French women as threatening or manipulative and having poor taste. Only in the early hours of the morning does Z get a good look at the French woman, and is pleasantly surprised at having discovered an exceptional woman, exceptional at least for a white woman.

Physically, the unnamed French female love interest is described as having a kind of “quiet charm” in her eyes, with an “erect nose” that “seemed to make her cheeks appear even more delicate.” Z pays close attention to her “small, fine mouth” and “her pointed upper lip,” her “beautiful teeth that are so rare among the French people,” and “her lovely graceful smile. The French woman has none of the typical physical attributes of a Western woman, save the erect nose; instead, her delicate features place her closer to traditional Chinese ideals of femininity. Once Z gets closer to the French woman, he admires her personality and points out her “gentle vivacity” (wenrou huopo) and “active stillness” (nengjing nengdong) (128), qualities that render her far from the aggressive sexual predator associated with the modern-girl figure. In fact, there is little that marks the French woman as exotic or foreign, but compared to her, the young Chinese woman K pales in terms of charm, both physically and in personality. Z explains that K has a very plain face, except for her eyes, which are “slightly enchanting” (120). To add further insult, he says that her physical appeal “only comes across when she moves around. If one just stared at her trying to paint her portrait, she really would not have any charm at all.” K’s romance with the Dutch artist is short-lived, and when she tries to explain to Z the reason for her initial attraction, she says haltingly, “I don’t know, for some reason, I just think that westerners are better at pleasing others (xian yinqin)” (135). By the end of the story, K conveniently comes to her senses to reunite with Z.

In fact, if any character is rendered exotic, it is the narrator Z, whose allure can be partially explained by his nonchalance, his utter lack of desire to “please” his women. Unlike Fu Lei’s narrator, who is never acknowledged or registered by white women, in Xu Xu’s story the French woman is the one who is insecure and has initial doubts as to whether Z is even attracted to her. Asked why he does not demonstrate his affection for her, he responds, “Because I’m an oriental,” which leads her to ask, “Is this how orientals love?” (129). She then questions why he always pays for her meals and for tickets to performances, and he informs her that in China groups of two or three commonly go out and treat each other, without regard for sex. Z’s ingenious romantic strategy of maintaining indifference while highlighting his cultural difference is remarkably effective in heightening the Frenchwoman’s desire for and attraction to him. This process of self-exoticization emphasizes the narrator’s difference from the typical western European male, as represented by the Dutch artist. Z is also an art connoisseur, as demonstrated at the beginning of the narrative when he appreciates the artist’s skill in sketching their likenesses and in accurately capturing their spirit when arriving at the café, as well as discerning that many of the artist’s later works no longer live up to this aesthetic standard.

By the conclusion of “Montparnasse Studio,” Z emerges as the clear sexual victor, managing to “steal” the French woman from the Dutch artist. Momentarily seduced by the artist, K decides in the end to leave France for England with Z and his French lover. Upon closer examination, however, Xu Xu’s story is less about the plight of the modern woman than it is about highlighting Z’s moral superiority to his Western male rival in his treatment of women. The issue of marriage appears repeatedly throughout the essay as a point of debate between the narrator and the two female characters. Although K and Z are both under the impression that the French woman and the Dutch artist are married, the French woman tells Z that it would not help her financial situation to marry a foreigner. When he responds sarcastically, “Then you think your current situation is so fortunate?” (127), he implies that their cohabitation outside of marriage is somehow immoral. She explains that the alternative, to be a shop girl, would be even worse, and that she is trying to pass her exams in order to have a real career. Upon hearing her lofty goals, Z automatically assumes, “So that means you don’t plan on marrying?” (128), to which she replies, “One day, of course I’ll marry, as long as I find a suitable French man.”

The topic of marriage is structured as a point of intercultural debate over the question of how to express love: is it through physical demonstration of affection in the “Western” style, or in the less demonstrative “Eastern” way? And, as the French woman asks Z, must love necessarily lead to marriage? Clearly, the motivation for marriage was a topic that Xu Xu himself found disconcerting—another xiaopin wen in the same collection is entitled “Reasons for Marriage” (Jiehun de liyou). The narrator of “Montparnasse Studio,” indignant that the Dutch artist has exploited his French partner to play three roles as “wife” (albeit not legal), “model,” and “French language tutor,” nonetheless rationalizes that his relationship with the French woman is entirely different. The woman affirms this, telling Z repeatedly that she finds herself unable to part from him and explaining: “I think I can’t leave you, when I’m with you I experience an especially liberating feeling.” Z tells her this is because he is not pursuing (zhuiqiu) her, presumably in the manner of the aggressive Dutch artist. The narrative logic demonstrates how the strangeness and exoticness of the oriental man—qualities that might easily be negatively perceived as passivity can become the source of moral superiority and even sexual desire.

The trope of a white woman choosing a Chinese man over his western European male rival reappears in “The Duel,” in which a French man referred to as F challenges the protagonist Z to a duel for the affections of a French woman named Kaisaling (most likely a transliteration of the name Catherine), who is referred to simply as “C.” Catherine is first described simply as having a “still beauty” (141) that is exceptional for someone her age: “It is truly rare for a twenty-year-old girl with such a healthy young body to have such a quietly beautiful soul” (141). Her spiritual and emotional reserve appears to be at odds with the youth of her physical being and its potential for unbridled (especially sexual) vigor. But later Z dismissively remarks, “I didn’t notice her all that much” (142). Catherine is exceptional, then, only in her ordinariness, and her otherness is rendered through her difference from the modern girl’s bold sexuality.

The narrative is centered on defining the labels “oriental” and “outdated,” whose binary opposites are presumably “Western” and “modern.” However, in the story, the boundaries of these categories are not strictly defined. To begin with, Z introduces the male French character F by describing his seemingly excellent qualifications as a well-rounded modern man: “He was a lively journalist, fulfilled every kind of amazing requirement, excelled at hunting, fishing, skiing, swimming, traveled frequently, was a fantastic photographer, could even do a little sketching and play the piano” (141). But these qualifications do not impress Z and are not enough to sustain Catherine’s affections. He then points out F’s inadequacies: “But I felt that he did not truly understand art, he did not enjoy listening to classical music, he didn’t love watching formal theater, nor did he love attending famous art exhibits” (141). Here, Z’s ideal modern man seems to embody traditional wenren characteristics: music appreciation is qualified as (Western) classical music, theater must be “formal” (zhengshi) as opposed to popular or vernacular drama, and the art exhibits must be those of well-known artists. F, on the other hand, is portrayed as embodying wu or martial qualities (hunting, fishing, skiing, swimming) and his more intellectual pursuits are described offhandedly as casual, lacking any kind of depth or true appreciation.

Chapter 2 flashes back to the initiation of Z and Catherine’s romantic relationship and their first meeting on a Sunday morning when the quintessential wenren narrator is in the midst of composing “a poem expressing the kind of nostalgia (xiangchou) one feels at night” (144). Catherine arrives at Z’s apartment to return his classroom notes, which she borrowed earlier to copy, and she reassures him: “They’re good, but there are many instances of Sinicized French (Zhongguohua de Fawen), which I couldn’t resist correcting a bit. I managed to infer your meaning though” (145). Z is offended, of course, but her redemption comes in the form of her inquisitive nature, for unlike the women in Fu Lei’s travel writings who display no interest in the male traveler’s intellectual prowess, Catherine’s curiosity is piqued on discovering the pile of writings on his desk. When Z tells her they are poems, she asks for clarification, “What do you mean ‘poems’?” He responds by telling her the genre, “nostalgia” (xiangchou) (146), which inspires her demand that he translate the poems for her to hear.

Talking about poetry and sharing photographs of his ancestral village trigger a discussion about the differences between relationship customs and preferences in China and the West that Z then confesses are the true source of his homesickness. Z pinpoints this exchange as the start of their friendship, and as time passes Catherine’s desire for Z grows in proportion to her perception of Z’s poetic ability. In Chapter 3, the homesick and lonely Z falls sick with delirium, waking only to scrawl a quatrain on his wall: “The wutong tree shows a new bit of green. Green, like the jade on your earlobes. Hence, that is the rain at dusk. Rain, like a teardrop at the eye’s corner” 梧桐上新露ー點綠,/ 綠,那是你耳葉上的翠;/ 於是那黃昏時候的 雨,/ 雨,那是我眼角的涙 (147). Evoking the literary trope of the wutong, or parasol tree, Z links his personal experience of being in Paris during a miserable and rainy winter with a familiar symbol of rain and sadness in the classical poetic tradition. Catherine’s appearance at his bedside during his illness is reminiscent of the blonde goddess that supposedly rescued Li Jinfa from his deathbed; her healing power lies in her obsession with Z’s poetic ability, which, with his guidance, she seizes upon as an essential part of his oriental identity.

Seeing his poems on the wall, she asks him to read and translate them for her. Ironically, although she saw him writing poetry on their previous encounter, she asks him why he never told her he is a poet. Somewhat contradictorily, he denies he is a poet and tells her that he didn’t reveal his writing of poetry to her because she isn’t able to read Chinese. But then she argues that his poems are “exceptionally rich in poetic sentiment” (148), a quality she has presumably inferred from his translation, to which he replies, “The Chinese are a poetic race, for if we call them poets, then everyone in China would be considered a poet.” His feverishly inscribed poem inspires Catherine to return the next day, wearing a pair of green earrings and hoping to “cure” him of his homesickness with her new look. Z counters, “But your outfit has no oriental sentiment” (dongfang de qingdiao) (149), a look that can be acquired only from studying Chinese landscape painting, he informs her. After studying the Chinese paintings in his collection, mementoes his friends gave on his departure from China, Catherine “fell in love with oriental sentiment, and also fell in love with me” (149). Z is the embodiment or essence of qingdiao, as shown in his affinity for the most easily recognizable and identifiable wen practices of poetry and painting.

In “The Duel,” the non-Chinese identity of Catherine comes to the forefront when F fails to show up at the appointed time for the duel against Z. Instead, Z sees the French couple strolling together intimately, and Catherine does not respond to him when he calls out to her. Angrily, the narrator refers to her as “that foreign woman who pretended to love me” and admonishes himself for falling for her when “there were so many close friends who truly loved me back in my hometown” (155). Presumably these are Chinese women who would demonstrate a purer and truer love, compared to the dishonest or inauthentic love of Catherine. On the surface, this is an obvious critique of Catherine’s deceitful character, but it is also the narrator’s self-critique, for although Catherine is guilty of stringing Z along while continuing her relationship with the French man, Z is guilty of falling for the charm of a foreigner, in essence betraying his love for the people in China. The sense of betrayal reappears a few pages later in the story, when Catherine refers to herself as “foreign woman” (159). She chides Z for not telling her about the duel and for risking his life for her love: “How could you be willing to die for a foreign woman (yizu de nüzi)?”

“The Duel” concludes with a letter from Catherine to the French rival F: “Dear F, This matter of letting God choose between two men who cannot coexist is a story from an outdated novel. So I put the choice in my own hands; the spirit of twentieth century France is fraternity, peace and liberty; I actually put it into practice, F. I will accompany Z on X day and X month and will have already arrived in England by the afternoon. C” (161–162). In choosing her lover, Catherine is depicted as the ideal modern woman; like the unnamed French woman in “Montparnasse Studio,” her act of leaving with Z is described as one that ironically grants her the ultimate freedom. It is important to point out that Z, like F, represents contrasting outdated notions of chivalry, romance, and honor. For example, Catherine criticizes Z’s willingness to die for her as “a relic of the Middle Ages” (161–162). The exoticism of Xu Xu’s white female characters lies, then, not in their physical appearance, brazen sexual behavior, or demeanor, but rather in their sexual attraction to the exoticism of oriental sentiment, typically indicated by markers of wenren culture. Sexuality in Xu Xu’s stories can be traced back to the narrators’ insider knowledge of Chinese culture, such as their perceived connection to traditional art and poetry. Their cultural capital conveniently acts as an aphrodisiac to their white female love interests, who possess a strong desire to both understand Chinese culture and recognize the intrinsic value of the modern wenren’s specialized know-how over his white European male counterpart.

Chang Yu’s Nudes: Challenging Racial Identity and Advocating a New Aesthetic

In 1946, the Parisian journalist Pierre Joffroy published a piece on the “inventor of ‘I’essentialisme,’” Chang Yu (or as he was known in France, Sanyu or San-Yu), in Le Parisien Libéré: “The curious could ask if San-Yu is a Chinese who is an artist or an artist who is Chinese. There is no answer to this question. The particular gift of this artist is to unite East and West in his painting, not in a confused sacrilegious hodgepodge, but in a sublime form where one loses usual points of reference.” The headline featured his name in all caps, and underneath, two subheads: “peintre chinois de Montparnasse” (Chinese painter of Montparnasse) followed by “ne peint ni en français ni en chinois” (paints in neither French nor Chinese). The way that his contemporaries and art historiography have portrayed Chang Yu as a liminal figure caught between two cultures is the product of both Chang’s aesthetic sensibility and his unusual persona as an expatriate artist. Although Joffroy’s article succeeds in pointing out the challenges associated with assigning racial identity to the practice of painting in, for instance, its problematization of the syntactic order of the labels of “a Chinese [who happens to be] painter” versus “a painter [who happens] to be Chinese,” the French print media consistently defined Chang Yu by his Chinese-ness, touting him as a Chinese painter and using his ethnicity as a marketing point. As an artist whose public persona was constructed as a painter torn between dichotomies of modern versus traditional and French versus Chinese, Chang Yu was routinely scrutinized for not fitting neatly into any of these binary categories. With the distorted and exaggerated figure of the white woman, he developed an inventive way to push viewers’ horizons, encouraging them to imagine how their notions of beauty could be transformed and advocating for a new standard of beauty.

Chang Yu was raised as the quintessential wenren. He was born on October 14,1901 in Nanchong, Sichuan to a relatively prosperous family that owned a large silk mill. As a youth, he studied painting with his father and calligraphy with the Sichuan master Zhao Xi (1867–1948). He arrived in Paris in 1921 as an art student, after studying in Japan and spending a brief period in Berlin; he may have received some government support, but his studies were primarily funded by his family. Although the art historian Gu Yue (2009: 39) attributes Chang Yu’s “complete lack of interest in material gain” to the “desirable self-control of a Chinese literatus” and the “integrity and independence of a Chinese artist,” other art historians have interpreted Chang’s literati background as a crucial flaw. For instance, Eugene Wang explains:

Chang’s venture. . . is a story of missed opportunities. He was in the right place, Paris, and at the right time, the 1920s and 1930s. His sensitivity in adapting traditional Chinese art to new possibilities and idioms could well have made him a great modernist when European modernism was drawing inspiration from Asian art. Yet his lack of enterprise, his self-absorption and carefree hedonism—all traits associated with traditional Chinese literati—left him insensitive to the pulse and pressures of the art market. (Wang 2001: 151–154)

Along with Pan Yuliang (1899–1977), who also remained in Paris, Chang Yu was an exception among the Chinese artists who studied abroad in the West. His “failure” has been explained by way of his eccentric personality and his bohemian lifestyle, and his consorting with Parisian “locals” and contemporary Western artists, implying his isolation from Chinese contemporaries. To read Chang Yu’s lack of financial success (and therefore career) as one of “missed opportunities” loses sight of the key role that his wenren sensibility played in his artistic choices.

In an undated poem, Chang Yu observes wryly, “Autumn chrysanthemums are for poets to praise / At the drinking gatherings of the literati. / It’s a pity that the chrysanthemum here / Are only for the graves” (秋菊詩人賞,文人對酒杯,可憐此間菊,只供作人墳). He signed the work as a poet might, rather than with his usual artist’s insignia: “November 1, upon seeing the chrysanthemum (jian ju yougan)” (Wong 2001: 384). Consisting of one unrhymed quatrain, each five-character line in the customary classical form is written in thick brushstrokes of black painted over a white oil background. The unusual move to paint with oil on mirror most likely stemmed from a perpetual lack of funds to purchase canvas, but Chang Yu’s homesickness is clear. The artist juxtaposes the chrysanthemum’s revered cultural status and rich historical significance in China, where it is celebrated for its beauty and strength of endurance, with its underappreciated status in France, where it is referred to as “la fleur de mort” for its association with funerals and mourning. Usually depicted in a vase, the flowers are featured in many of his still-life oil paintings. The chrysanthemum is also ubiquitous in classical Chinese poetry, particularly in association with the reclusive life of the poet Tao Qian (365–427), and the poem’s second line, translated literally as “literati facing their wine cups,” alludes to Tao Qian’s drinking poems. The connection between Chang Yu and Tao Qian is significant. In 1930, Éditions Lemarget in Paris published an edition of selected poems by Tao Qian, translated from Chinese into French by Liang Zongdai (1903–1983); the limited-edition volume featured a preface by the poet Paul Valéry (1871–1945), and Chang Yu was commissioned to provide three copperplate engravings as accompanying illustrations.

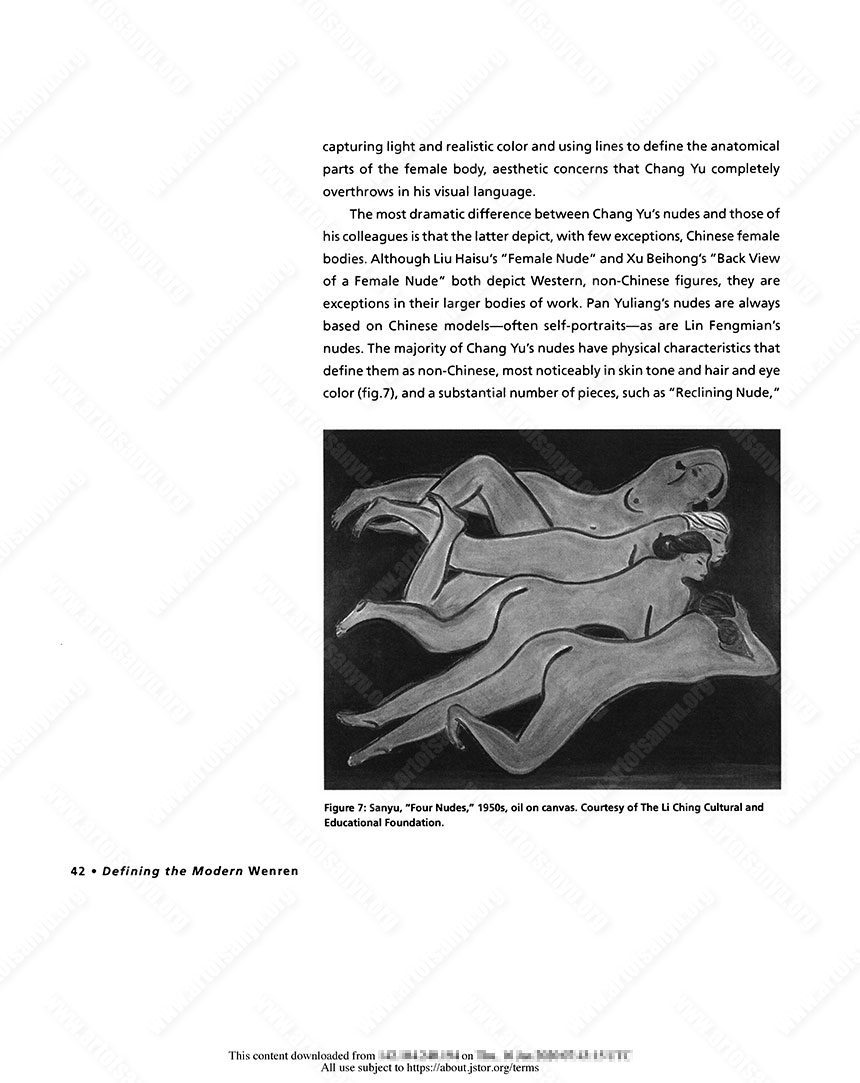

At first glance, Chang Yu’s nude paintings may seem imitative of works by his European modernist contemporaries, such as the Cubist painters Picasso and Georges Braque; however, his connection to traditional wenren culture, combined with his belief in a subjective appreciation of aesthetic beauty, allows for a more nuanced interpretation. In this section, I focus on the most striking difference between Chang Yu’s nude paintings and those of his fellow Chinese painters: whereas the latter depict for the most part Chinese female bodies, Chang Yu’s subjects are mostly white women. I argue that through distortion and exaggeration, Chang Yu’s nude paintings of white women challenge conventional Chinese ideals of feminine beauty and also the relationship between Western painting and realism.

Here, Eugene Wang’s discussion of the difference between xieshi (realism) and xieyi (literally “writing the intention,” sometimes translated as “free sketch” or “sketch conceptualism”) is instructive in exposing the fraying boundaries between these two representational modes. Drawing on Xu Beihong’s well-publicized comments on contemporary Chinese art written upon his return to China in 1926, Wang notes, “Realism emphasizes images and objects, while conceptualism concerns itself with mental states and emotions. Realism stems from close observation, while conceptualism thrives on sensation” (111). In discussions about the development of modern Chinese art practices, xieyi and xieshi have been set up as two opposing categories. Xieyi, the key philosophy in traditional Chinese art, relies on the artist’s spontaneity and expressivity that is possible only through literati amateurism. This subjective approach requires an interaction that calls for the viewer’s active participation and interpretation. Xieshi, by contrast, is cast as a modern, scientific approach, by which the artist faithfully conveys his or her objective vision of reality. In this mode, the artist’s skill is evaluated by achieving technical gongbi verisimilitude, not the ability to capture the subject’s spiritual essence.

The case of Chang Yu’s nude paintings, however, illustrates how misleading it is to argue that one mode is ultimately more modernist than the other. In many ways, the nude female form represents the quintessence of modernity in Chinese painting from the early twentieth century: “Partly because of its status as an imported Western idea, and partly because of its illicit overtones, the female nude quickly became one of the central symbols of modernity along with airplanes, radio towers, and cigarettes—other popular signifiers of technological and social ‘progress’” (Jones 1999: 226). The debate among male artists, politicians, and intellectuals in the 1920s and 1930s over the use of nude models in the Chinese art world took place on two different but related levels. First, conservatives objected to it morally. In the fall of 1925, Shanghai city councilor Jiang Huaisu wrote a letter of complaint to Minister of Education Duan Qirui: “Art school is not medical school. What importance is the structure of the human body and the process of life to art? Why does the appearance of the spirit have to be represented by a naked girl? Men and women all have human bodies. The students of the art academy are all male. Why can’t you use male models?”[5] Published on September 26, 1925, Jiang Huaisu’s letter was written in response to Liu Haisu’s proud radio broadcast and print proclamation that he was the first educator to adopt the use of nude models in art instruction in China. Jiang demanded that Liu Haisu, who was the director of the Shanghai Art School, be punished and that the practice of using female nudes models be abolished. Jiang Huaisu’s conservative position was eventually supported by Jiangsu warlord Sun Chuanfang, resulting in a temporary ban on nude models a year later.

As Jiang Huaisu’s letter reveals, the debate over nude models was centered particularly on the female body. He likens the female models to prostitutes who “use their bodies as a living specimen,” describing them as “shameless women” who “work naked in front of the crowd, reclining or lying down, bending into all sorts of positions.” His letter also points out how realism played into the debate. Although some intellectuals were quick to embrace Western painting technique for its scientific depiction of the human body and new modes of representation, such as photography, for their ability to capture the real, Jiang Huaisu did not see the appeal of mixing art and science: “In recent years, pictures of nudes were sold on the street, in photographic or in painted form, and all look just as though they were real.” By 1932, Fu Lei was affirming that “the use of nude models for research purposes in art studios has been formally and officially acknowledged” (Roberts 2010: 41), suggesting that the use of nude models needed some sort of scientific justification to overcome the moral objections.

Leo Ou-fan Lee traces the lineage between Western realism in Chinese art and the proliferation of images of “healthy” young women in pictorials such as Liangyou (The young companion, 1926–1945) back to their origins in erotica:

To move from the portrait of a fashionable woman to that of a female nude generated a further anxiety for readers living in that still transitional age, because drawings of naked female bodies in traditional Chinese culture were found largely in pornographic books. The invention of photography and its adoption by the modern newspaper and magazine added a mimetic dimension: the nude figure now looked like a real person. (Lee 1999: 73)

In this sense, the realist depiction of the female nude could be justified with the lofty goal of biological research. More recent scholarship on the bilingual monthly pictorial Liangyou has further elaborated on the representational figure of the healthy modern girl during the Republican era, including its relevance in women’s athletics (Cunningham 2013; Gao 2013) and in the popular scientific discourse surrounding the promotion of norms of modern femininity (Lei 2013). Images of the beautiful female body also frequently appeared in commercial art, such as advertisements and calendar posters, or yuefenpai, especially in 1930s Shanghai. Ellen Johnston Laing (2004: 219) explains: “Where once Western models of feminine beauty in décolleté dress as advertising images were rejected as ‘meaningless’ or even scandalous to the Chinese eye, now seminudity and bare breasts are approved, despite the fact that seminudity and bare breasts had long been sanctioned in certain genres of Chinese traditional art.” The nude body, by the time that Chang Yu was producing his nude oil paintings in the 1930s, was acceptable so long as it remained in the context of advocating a healthy standard of feminine beauty.

Still, this scholarship continues to neglect for the most part the significance of the figure of the white female body. One exception is Yingjin Zhang’s discussion of an illustration, entitled “The Heroine,” of a white female nude holding a Chinese sword that appeared in the October 1933 issue of Liangyou. In his analysis of this ambivalent painting, which is enigmatically subtitled “Resistance” (Fankang), he argues:

The female body is precisely such a site of multiple discourses and practices, a site where the male artist displays his unusual talent, the male viewer practices his exquisite connoisseurship, the male entrepreneur invests for financial gains, and the male adventurer tests his imaginary encounter with the West. Represented as artwork, commodity, and signifier of a cultural significant event, or any combination thereof, the female body in modern Chinese pictorials simultaneously constitutes a site for visual pleasure, a site for cultural consumption and discursive formation, and a space for articulating private fantasies, public anxieties and unresolved tensions and ambivalences. (Zhang 2007: 153)

Zhang’s study is structured around “a dominant male, whose viewing, among other things, denies or suppresses feminine desire and female subjectivity” (153), but in the case of travelers such as Chang Yu, can we safely assume that the male is no longer dominant once he is abroad? To press this issue further, what does a female Other look like as imagined by a male viewer whose own subjectivity is called into question?

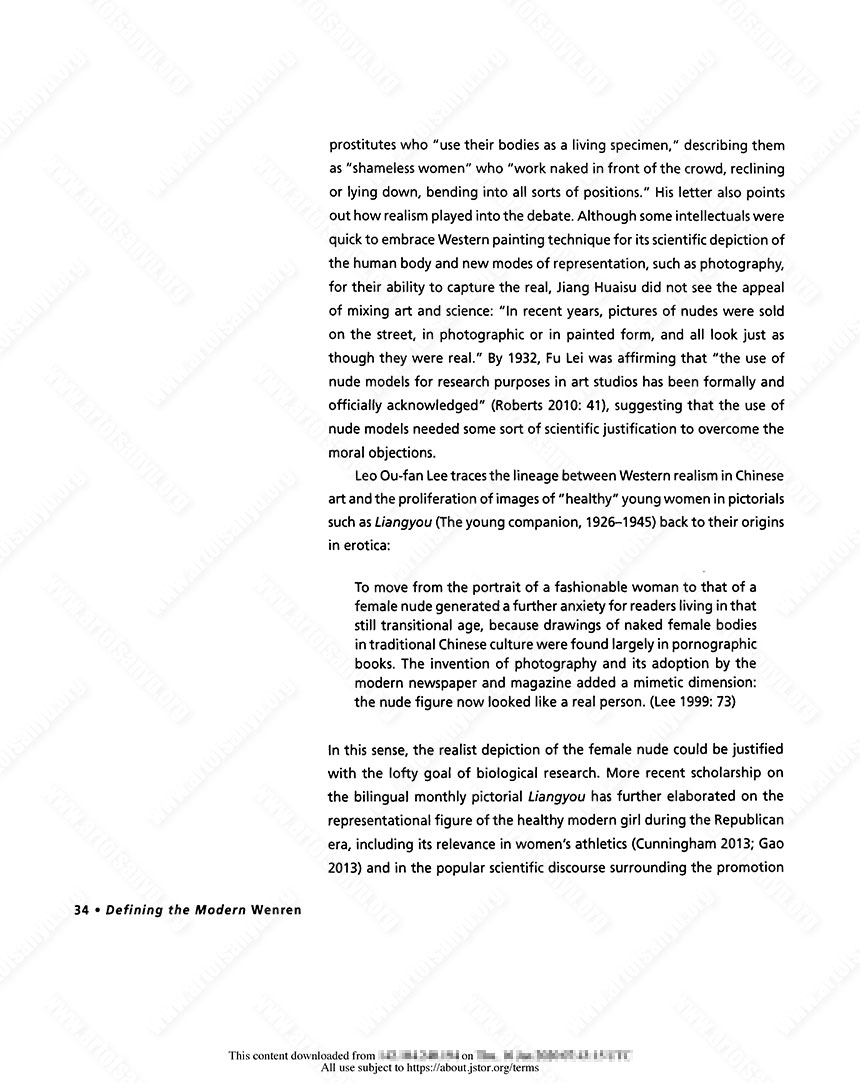

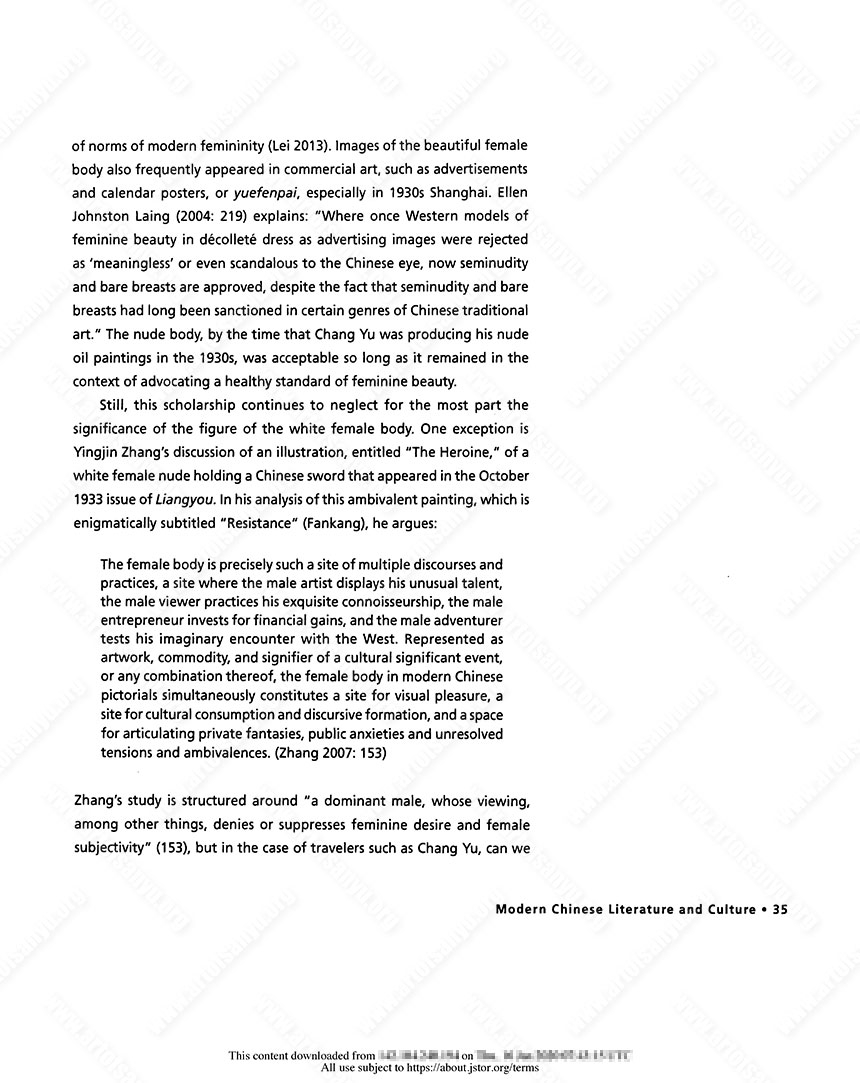

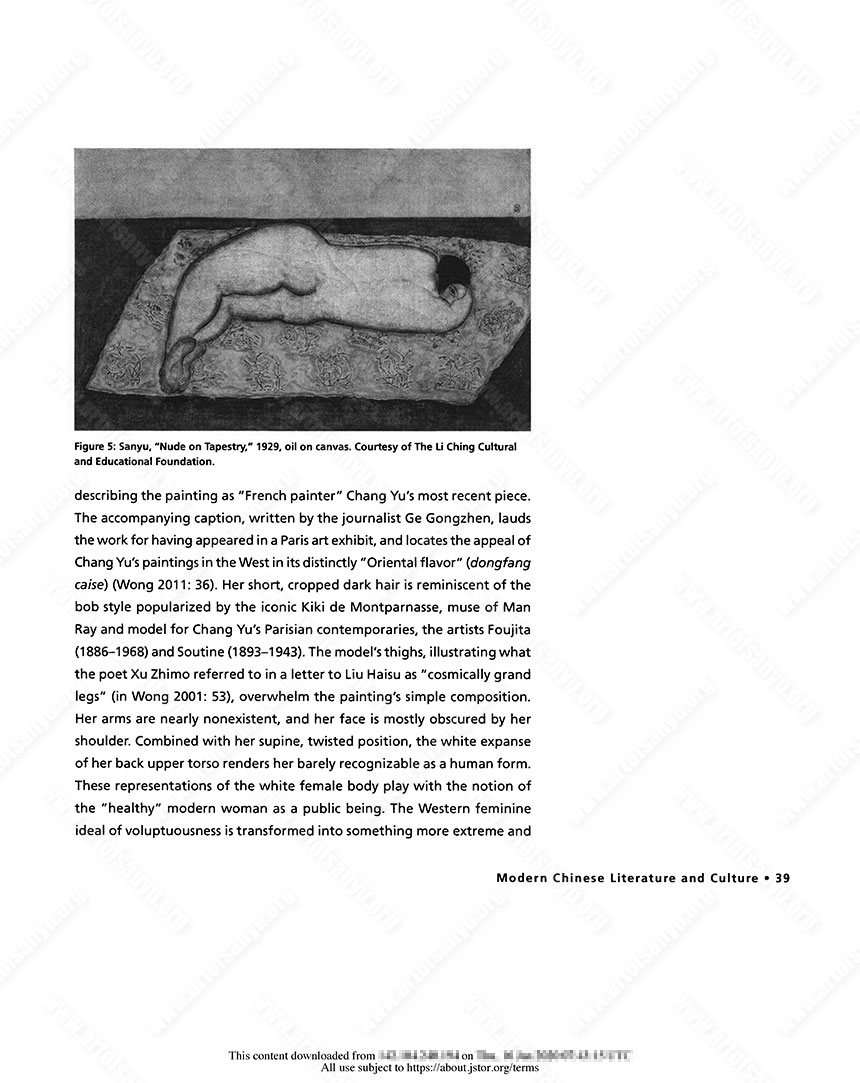

Surely Chang Yu was well aware of the intellectual debates about nude models taking place in China, because he was close friends with Xu Beihong and stayed connected through his relationships with other Chinese artists and writers, such as Pang Xunqin and Shao Xunmei (1906–1968), who were either passing through or residing in Paris. In 1928, the young artist created a sketch of his wife, a twenty-four-year-old French woman named Marcelle Charlotte Guyot de la Hardrouyère (fig. 2). Inscribed to her, the pencil-on-paper illustration depicts his former classmate at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, her large, piercing eyes looking straight at the viewer over the rim of a raised cup and under the brim of a cloche hat. The rest of her facial features are obscured, and the lower half of her body is invisible, truncated by one stroke delineating the table on which her elbows rest. Chang Yu’s training in classical calligraphy reveals itself in the curved linearity of her form and the undulating outline that encircles her body. Marcelle’s loosely flowing blouse or dress renders her instantly recognizable as a fashionable Western woman. One year later, Chang Yu would move from his earlier watercolor, ink, and charcoal media to painting his nudes in oil and enter his “pink period,” but during the transition the women in his works were most often clothed, usually wearing iconic 1920s accessories, such as Mary Jane shoes, pleated skirts, and cloche hats (fig. 3).

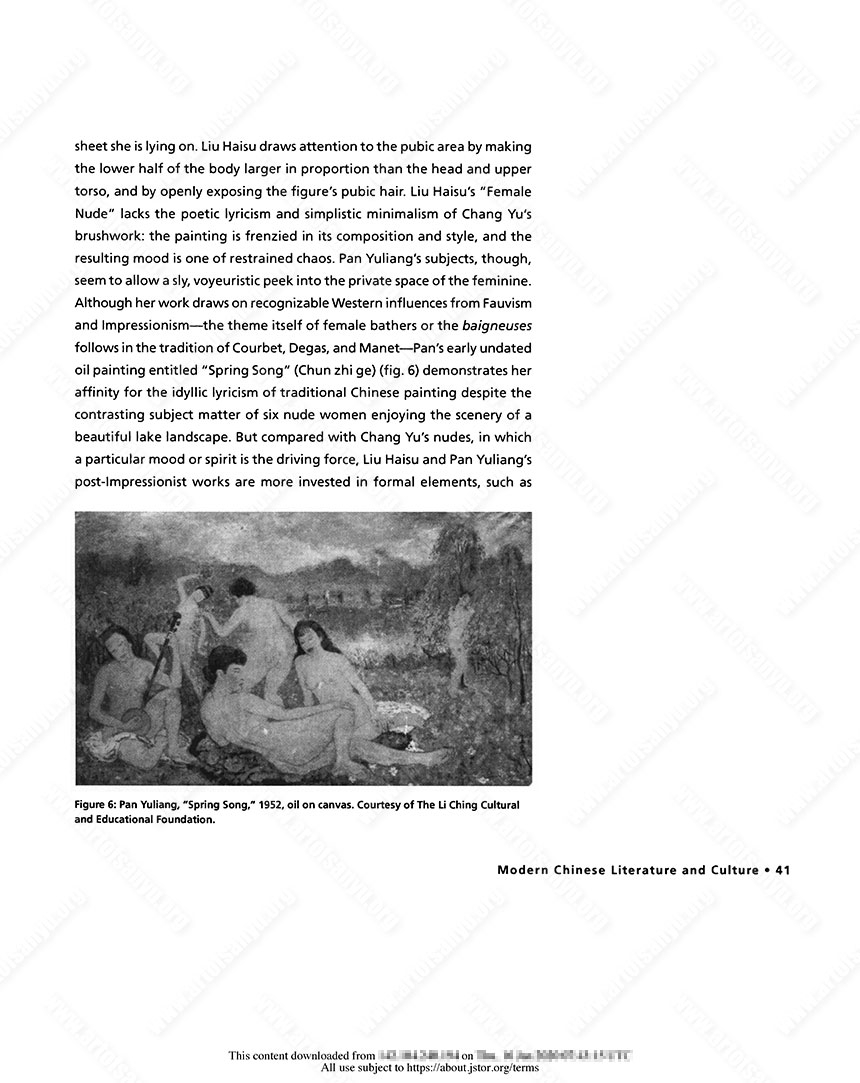

As Chang Yu began to paint in oil, however, his style became increasingly spare and he moved closer to what would become his trademark minimalist aesthetic. In 1932, Johan Franco, Chang Yu’s close friend and patron, summarized what he called Chang’s simplicisme in his preface to a brochure for an exhibition of Chang’s painting held at the J. H. de Bois Gallery in Haarlem, The Netherlands: “At first, his work gives most viewers a feeling of artlessness and only after long and repeated viewing makes a sincere and serious impression. He knows how to depict the essence and often the humour of things with astonishingly little means” (Sotheby’s 1995: n.p.). Chang Yu’s deliberate choice of oil over ink baffled some art critics, such as the Dutch critic Jan D. Voskuil, who wrote in a review of Chang Yu’s 1933 exhibition at the Galerie van Lier in Amsterdam: “Sanyu. . . attempts to create a certain effect in the oil medium. . . which would probably have been achieved more immediately with pencil or brush and ink. With the quick and sensitive hand of a Chinese calligrapher, he etches lines of flower baskets and horses out of the thick layer of oil. . . It is hard to figure out though why he needs to resort to oil to accomplish his creative purpose” (in Wang 2001: 140). Both of the aforementioned contemporary critics point to the spirit of spontaneity that is conveyed by his technique of sketch conceptualism and his oil medium as a characteristic that can be traced back to his classical training as a calligrapher, and the subsequent act of interpretation required of his viewer. As he switched over to the medium of oil, his nude paintings became almost entirely devoid of references to urban modernity. The female body seems to be a depoliticized, detached space on which he can experiment with only the essential elements: technique, color, and form.